Halliburton Tries to Greenwash Fracking November 17, 2010

Posted by Jamie Friedland in Natural Gas.Tags: 60 Minutes, Aubrey McClendon, Chesapeake Energy, CSI, EPA, Fracking, Greenwashing, Halliburton, Hydraulic Fracturing, Natural Gas

1 comment so far

Latest post at Change.org:

Some things just can’t be spun, but that doesn’t mean Halliburton won’t try. After being subpoenaed by U.S. EPA for refusing to reveal its drilling chemicals, the company announced it had developed a “green” fracking fluid sourced entirely from the food industry and promised to reveal the generic formula. That’s a start towards public disclosure, but far from good enough.

Full post here.

A Guide to Natural Gas Fracking September 13, 2010

Posted by Jamie Friedland in Natural Gas.Tags: Earthworks, fracing, Fracking, Halliburton, Halliburton Loop Hole, Hydraulic Fracturing, Hydrofracking, Natural Gas, shale gas

8 comments

Hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” is a drilling technique that has earned a lot of media coverage lately – especially in regard to natural gas. In the last couple of years, it has been credited with dramatically increasing U.S. and world natural gas reserves enough to potentially transform global energy markets previously dominated by coal.

However, there are warranted concerns about polluted groundwater near fracking sites most vividly demonstrated by videos of flammable drinking water arriving through kitchen faucets as shown in last year’s investigative documentary film “Gasland.” Yet the most recent fracking headlines came late last week when the Environmental Protection Agency instructed nine major companies to disclose what chemicals they use in the process.

Like many other energy and environmental issues, fracking is not a topic that lends itself to intelligible sound bites – background information is necessary to grasp and engage in the debate. Below, I have posted a number of questions and answers about fracking. If anyone has additional questions unanswered here, please feel free to post them and I will do my best to track down an authoritative answer. So, we begin with the basics:

What is fracking?

Let’s hear it from the horse’s mouth – in this case, Energy In Depth, an industry front group:

“Some oil and natural gas wells flow more easily than others. In many cases—up to 90 percent, in fact—it is necessary to stimulate well sites to allow the energy contained thousands of feet below ground to rise to the surface for collection. …By creating or even restoring fractures, the surface area of a formation exposed to the borehole increases and the fracture provides a conductive path that connects the reservoir to the well. These new paths increase the rate that fluids can be produced from the reservoir formations, in some cases by many hundreds of percent.”

Natural gas is the cleanest burning fossil fuel. Although it is not truly “clean” in terms of either traditional or greenhouse gas emissions, it is preferable to coal for electricity generation and, in compressed form, can be used instead of gasoline. Many people view natural gas as a short- to medium-term transition fuel on the way to a clean energy economy. That would require extensive natural gas resources, and hydraulic fracturing does provide access to vast additional reservoirs here at home.

Hydraulic fracturing can enhance recovery from traditional wells, but its primary benefit is enabling production of “unconventional” natural gas resources (described below). According to the Department of Energy, unconventional American natural gas resources have increased nearly 65% in the last decade – mostly as a result of technological advances (to fracking methods, although the concept has been around for 60 years) rather than discovery of new reservoirs. Already, unconventional sources account for 46% of current US natural gas production.

Why do we use fracking?

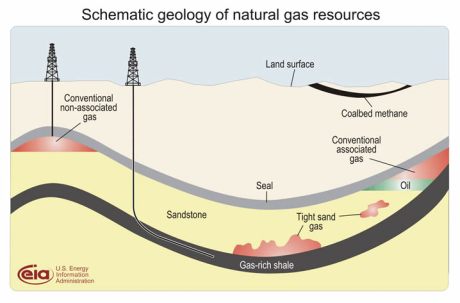

Like oil, natural gas forms deep underground. Its low density causes it to slowly rise through the earth from the depth at which it formed toward the surface. In some places, those hydrocarbons reach the surface in natural seeps like the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles. More often, however, the rising gas (and oil) become stuck beneath impermeable geological formations known as “traps.” Beneath these traps, gas and oil accumulate in high concentrations, or “reservoirs.”

In the graphic above, the gray “seal” is an impermeable rock layer. At the left side, it has formed a bend (which in three dimensions would be roughly dome-shaped) that has trapped upwardly migrating natural gas. This is what is known as a “conventional” natural gas reservoir. To obtain that gas, you simply drill a borehole straight down into the reservoir and pump it out. The source rock beneath the trap is porous (like limestone) and small channels between pores enable gas to flow through the rock. Visualize the drilling apparatus as a straw sucking out liquid; more liquid from deeper in the reservoir gets pulled in as the pumping continues.

The darker gray band in the graphic contains a shale formation rich in natural gas. Shale gas is an “unconventional natural gas” resource. It is defined by its low permeability, and gas cannot flow easily through it. A vertical borehole would not access a significant quantity of hydrocarbons because the gas is separated into isolated pockets within the rock. This is a bit more abstract, but now visualize trying to use a straw to extract juice from a grapefruit. You can access the pockets you pierce with the straw, but sucking will not help empty any pockets you have not directly punctured.

Of course, shale is not a grapefruit. It is a sedimentary rock, so it has many horizontal layers deposited over time. When stressed, the rocks tend to fracture vertically, opening up pore space between many different pockets. Drillers can access economical quantities of gas by drilling horizontally through a shale play and using hydraulic fracturing to open up those vertical fractures.

How does fracking work?

As in the graphic below, to economically extract natural gas from a shale formation, a borehole is drilled down several thousand feet to the desired depth. Oftentimes the well then turns horizontal, drilling a long distance laterally within the shale play. Then the well is cased like a normal well: steel pipes are inserted and then surrounded by cement. After that, a “perforating gun” is lowered into the well at depth. It contains explosives designed to blow through the steel and cement in certain locations at production depth that will enable hydrocarbons to flow into the pipes. Once the perforating gun is fired, then the fracking can begin.

A combination of water and other chemicals, many of them toxic, are pumped into the well at very high pressures – enough to break the rock. This “fracking fluid” is designed to cause more fractures in the rock and expand them to reach more pockets of oil and gas within the shale formation. Sand or other similar particles are used as a “proppant” to keep the fractures open so that gas and oil can flow through (the high natural pressure at these depths would otherwise close the fracture channels once the fluid was drained). Then production can begin/continue.

This video, also from Energy in Depth, explains the process:

How is fracking dangerous/why do people oppose it?

Fracking requires massive quantities of water. According to the Department of Energy, hydraulic fracturing in a single well generally uses 2-4 million gallons of water. Although clean water is cheap and plentiful in America today, freshwater is not an unlimited resource. Scaling up fracking would consume billions of gallons of water. Even without using billions of gallons of clean water to get natural gas, 1/3 of all counties in the US are projected to face water shortages by midcentury and more than 400 of those counties face extremely high risk of water shortages.

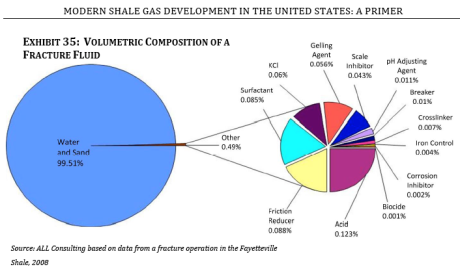

But the more serious immediate concern is the “fracking fluid.” Along with water, companies that employ fracking inject toxic chemicals into the ground. What chemicals? We’re not entirely sure. Fracking fluid is largely unregulated, so they could be nearly anything. We know a few, and there are other reports of chemicals that pose both immediate and chronic health risks. But drilling companies have long objected to disclosing the toxic chemicals they inject into through* (sorry about the careless phrasing) our groundwater, comparing asking for a specific list to asking Coke to give up their secret formula. Except when Coke spills, it doesn’t kill 17 cows or poison fish. We don’t know exactly what these chemicals are, but we know what they do.

The industry assures us that their fracking fluid is safe. But surely some of these chemicals, perhaps the “biocide,” for example, are dangerous if they migrate into our groundwater as they have done before.

Industry groups like to downplay safety risks by mentioning that more than 99% of the fluid used in fracking isjust water. But remember, a single well can use 2-4 million gallons of water, so that still means 20,000-40,000 gallons of toxic chemicals. And whatever those chemicals are, we know they can leak from a well into the groundwater from which we drink, they have proven lethal to animals, and they have already proven to have significant health impacts for people as well – even just from showering in contaminated water.

Until we know what’s being put into our water, it is fully reasonable that communities near fracking sites are resisting the practice. Earthworks has a good list of fracking myths and facts that help detail the concerns.

Where is fracking being used?

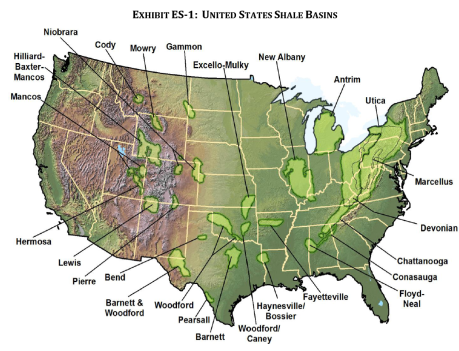

There are sizable shale formations around the country from which natural gas could be extracted with hydraulic fracking (see map below). One of the most promising is the Marcellus Shale formation centered over Pennsylvania and New York. The most vocal opposition is currently in New York, where this week, concerned citizens will have the chance to halt fracking until they are told exactly what chemicals the drilling companies want them to drink.

Shale basins around the country contain recoverable natural gas reserves. Fracking is becoming an industry standard, so federal regulations – or lack thereof – have a significant impact from sea to shining sea.

Is fracking regulated?

Yes and no. Technically, a number of federal laws regulate fracking. The Clean Water Act regulates the surface discharge of wastewater and storm water runoff. The Clean Air Act limits airborne emissions from engines as well as drilling and processing equipment. Additionally, the National Environmental Policy Act requires companies to analyze the potential environmental impacts of exploration and production.

There is a notable exception from this list: the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). What about the toxins injected underground? The SDWA rightly regulates toxic chemicals injected into our drinking water. Unfortunately, as Earthworks explains, fracking fluid is specifically exempted from this regulation by the “Halliburton Loophole” in the 2005 Energy Act:

“Despite the widespread use of the practice, and the risks hydraulic fracturing poses to human health and safe drinking water supplies, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) does not regulate the injection of fracturing fluids under the Safe Drinking Water Act. The oil and gas industry is the only industry in America that is allowed by EPA to inject known hazardous materials — unchecked — directly into or adjacent to underground drinking water supplies.

This exemption from the SDWA colloquially bears Halliburton’s name because it is widely perceived to have come about as a result of the efforts of Vice President Dick Cheney’s Energy Task Force. Before taking office, Cheney was CEO of Halliburton — which patented hydraulic fracturing in the 1940s, and remains one of the three largest manufacturers of fracturing fluids. Halliburton staff were actively involved in review of the 2004 EPA report on hydraulic fracturing.” -Earthworks

Halliburton (and the Bush administration) justified this exemption by advancing the claim that all fracking fluids are extracted from the well and thus do not enter the groundwater. They have argued in court that these chemicals are both safe and not left underground anyways. That is not true. The toxicity of fracking fluid components is discussed and linked above, but a recent investigation also revealed that up to 85% of fracking fluid is indeed left underground where it can and has seeped into drinking water supplies.

Fracking currently enjoys an additional exemption from reporting fracking fluid chemicals under the 1986 Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act. Fortunately, the EPA is now reviewing the safety of this practice.

Fracking and natural gas may well have an important role to play in our energy future, but from fracking pollution to the recent oil spills (plural) and the California gas line explosion, it is clear this industry is in need of modern regulations.

The Political Climate is now on Twitter! Follow @PoliticalClimat for updates as well as daily tweets linking to important and under-reported environmental news.

Deeply Flawed Ruling Overturns Deepwater Drilling Moratorium June 24, 2010

Posted by Jamie Friedland in Offshore Drilling, Politics.Tags: BP, Deepwater Horizon, Drilling Moratorium, Halliburton, Judge Feldman, Louisiana, Martin Feldman, Obama, Offshore Drilling, Oil Spill, Political Climate, Transocean

2 comments

***UPDATE: Rachel Maddow has reported more information about Judge Feldman’s oil-related investments here.***

On Tuesday, Judge Martin Feldman granted a preliminary injunction brought by the oil industry against the Obama Administration’s 6-month moratorium on floating offshore drilling in the Gulf of Mexico. That ruling lifts the drilling ban.

First of all, it is significant that Judge Feldman has reported extensive investments in the oil industry including both Halliburton and Transocean. Shockingly enough, his ruling does not read like it was penned by an impartial arbiter. He uses phrases like “the government admits that the industry provides relatively high paying jobs” (p. 5-6). Like that has anything to do with the safety of offshore drilling.

In describing the Deepwater Horizon disaster, Feldman even uses the exact same analogy trotted out by conservative pundits; “Are all airplanes a danger because one was?” (p. 19). He also adds a few more analogies, including my personal favorite: “[Are] all tankers like Exxon Valdez?” (p. 19). YES, FELDMAN, ALL THE SINGLE-HULLED TANKERS IN THE WORLD ARE JUST LIKE EXXON VALDEZ. That’s why we’ve switched [embarrassingly slowly] to using double-hulled tankers!

Judge Martin Feldman. One of the 37 out of 64 active or senior judges in key Gulf Coast districts that have ties to the oil and gas industries.

Having read Feldman’s 22-page ruling, I am less than compelled by his arguments.

As I explained in my earlier defense of the moratorium, the logic for temporarily suspending deepwater drilling operations is very clear:

-Fact: We do not yet know what caused the blowout that sank the Deepwater Horizon rig.

-Fact: We do not have adequate prevention or containment methods for a deepwater blowout, so a massive oil spill is guaranteed if a blowout occurs.

-Fact: A massive oil spill is unacceptably destructive.

-Conclusion: Deepwater drilling must be halted AT LEAST until we know how to prevent and/or recover from deepwater blowouts.

Nobody has presented a counterargument to this logic. This ruling does not contain one. I don’t believe that one exists.

The oil industry and indeed Judge Feldman argue that the moratorium is a punitive action against innocent oil workers and that it would cause excessive job loss. This is false. Judge Feldman writes:

“Oil and gas production is quite simply elemental to Gulf communities” (p. 6).

As nice as that non sequitur would look on an oil billboard, all that says is that these communities need to diversify.

Employment has nothing to do with the justification for this moratorium. Even if it did, I have shown that blowouts such as this cause far more job loss in sustainable industries such as fishing and tourism than the moratorium would temporarily cost the drilling industry.

I find further faults in Judge Feldman’s ruling.

From a legal perspective, the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act instructs the Secretary of the Interior to prescribe regulations,

“for the suspension or temporary prohibition of any operation or activity, including production…if there is a threat of serious, irreparable, or immediate harm or damage to life (including fish and other aquatic life), to property, to any mineral deposits (in areas leased or not leased), or to the marine, coastal, or human environment.” (p. 7-8).

This oil spill meets EVERY ONE of these conditions, ANY ONE of which justifies a moratorium.

Now, that same piece of legislation also preserves the right of any person “having a valid legal interest which is or may be adversely affected” by such regulations to sue to stop them (p. 8). But those adversely affected workers do not make our oil rigs any safer or in any way reduce the threat that validates the moratorium. If they have suffered financial burdens, make BP and friends compensate them. Case closed.

The Administrative Procedure Act cautions that an agency action may only be overturned if it is “arbitrary” and “capricious”. Lo and behold, Judge Feldman found this moratorium both arbitrary and capricious.

This moratorium is anything but arbitrary and whimsically impulsive.

Feldman contends that the government did not examine alternatives to the moratorium. But until we know what caused the spill, there is no other effective preventative measure than not drilling (aside from blindly hoping it doesn’t happen again before we figure out what happened, but that’s not what I consider “effective”).

Feldman explains his ruling with the contention that the MMS report outlining the proposed drilling reforms “makes no effort to explicitly justify the moratorium: it does not discuss any irreparable harm that would warrant a suspension of operations” (p. 4). Seriously Feldman? Are you joking? Have you read the news in the last two months? You live in Louisiana for crying out loud. Oh! I know, check the performance of your oil stocks. Notice anything different? Ya, something big happened. It has consequences.

Feldman goes on to condescendingly demonstrate Secretary Salazar’s “pattern” of implying the catastrophic effects of deepwater drilling without explicitly stating them.

Instead of explaining the most convincingly implied point I have ever come across, I will take this moment to explicitly proclaim Judge Bubby Boy either decidedly dim or of integrity as oily and compromised as a deepwater blowout preventer. Take your pick.

The points of contention continue.

Feldman repeatedly refers to the Administration’s “blanket” moratorium on offshore drilling. If you’ve been following the oil spill, you may recall an earlier “mini-scandal” when the moratorium was announced: Secretary Salazar assembled a panel of experts to review the proposed safety reforms. Those experts approved – among many other reforms – a six-month moratorium on exploratory wells deeper than 1000 feet. The final report proposed a six-month moratorium on exploratory wells deeper than 500 feet. Everyone freaked out about DOI’s “blatant misrepresentation” of the experts’ recommendations (of which the moratorium was a small fraction).

Now, aside from sounding so far from impartial as to seem personally offended by these events, Judge Feldman wrote:

“[Eight of the experts] have publicly stated that they “do not agree with the six month blanket moratorium” on floating drilling. They envisioned a more limited kind of moratorium, but a blanket moratorium was added after their final review, they complain, and was never agreed to by them. A factor that might cause some apprehension about the probity of the process that led to the Report.” (p. 3)

First off all, that last sentence sounds like the script for a Fox News anchor. My complaint here is for those experts that oppose the moratorium as well: just what kind of moratorium would you propose? 500 feet is the switchpoint between rigs that rest on the ocean floor and floating rigs. That is, in Judge Feldman’s own words, “undisputed” (p. 18).

The oil industry (in this case, including Judge Feldman) isn’t angry that the Department of the Interior changed the moratorium depth by 500 feet. They’re angry that it was implemented at all. People talk about this “blanket moratorium” as if Obama tried to stop all offshore drilling. In fact, he attempted to do nothing of the sort.

Feldman writes that he “is unable to divine or fathom a relationship between the findings and the immense scope of the moratorium” (p. 17). Recurring oil spill delusion aside, “immense scope?” Let’s look at what we’re talking about here.

The term “blanket” moratorium by itself is misleading. The moratorium applied only to floating oil rigs drilling exploratory wells in depths deeper than 500 ft. Existing production at those depths continued unaffected. Shallower offshore drilling (the vast majority of offshore drilling) was unaffected. The moratorium only applied to 33 oil rigs out of the ~4500 currently drilling in the Gulf!

How much more limited could the moratorium get? Should it only apply to deepwater wells owned by BP? Only deepwater wells cemented by Halliburton? Only deepwater wells operated by Transocean rigs? How about only those deepwater rigs that are about to explode and sink?

WE DON’T KNOW WHAT CAUSED THE BLOWOUT; how could we possibly refine the moratorium further? “Immense scale?” This is the loosest-weave “blanket” moratorium in history.

Judge Feldman himself wrote that, “It is well settled that “preliminary injunction is an extraordinary that should not be granted unless the party seeking it has clearly carried the burden of persuasion” (p. 13). That has not happened. Yet Judge Feldman today rejected the government’s appeal to his Tuesday ruling. In doing so, he refused to delay his lifting of the drilling moratorium. Why? For “the same reasons” given in his prior ruling. God bless America.

Full list of oil spill questions and answers here.

Oil Execs Testify Before Congress…Technically May 11, 2010

Posted by Jamie Friedland in Offshore Drilling, Politics.Tags: 2010 Oil Spill, BP, cantwell, Congress, Deepwater Horizon, EPA, Gulf of Mexico, Halliburton, ixtoc, landrieu, menendez, Montara, murkowski, Offshore Drilling, Oil, Oil Spill, Senate, sessions, testimony, Transocean

3 comments

In case you didn’t have the pleasure of watching executives from BP, Halliburton and Transocean testify before Congress Tuesday afternoon, I have compiled some highlights and thoughts below.

The testimony in the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy & Natural Resources was revealing in how little it revealed. If we are to learn from and respond to this tragic event, people will have to start changing their tunes. As of today, they have not. I mean that in respect to both the oil executives and many of our U.S. senators. We’ll do the Big Oil execs first, then get into the senators.

First, the Big Oil execs:

If you have watched this kind of congressional testimony before, you know it is the world’s most boring dance. Senators ask questions, and those testifying carefully choose their words to convey as little as possible – or claim memory loss. Sometimes a senator will pursue an answer, but rarely does that actually extract the desired truth.

The only questions Big Oil actually answered today were those that Google could just have easily have answered, such as “is your company the largest offshore drilling contractor?”

Corporate legal teams carefully prep their executives to legally dodge the most damning questions. That preparation, which largely defeats the purpose of these hearings, was on notable display twice this afternoon.

For over a week now, BP has said it is prepared to pay “all legitimate claims.” They’ve been talking a big game about how they plan to repay their victims.

Conveniently, BP has yet to define exactly what claims it considers “legitimate.” They are unlikely to do so until they are taken to court. In his testimony, when pressed on this question, BP America President Lamar McKay did nothing but repeat that deliberately ambiguous phrase.

When general prodding from several senators went unanswered, Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) finally tried to hold BP accountable. She went down a list of likely claims against BP. McKay’s response was the same nearly every time: “all legitimate claims.”

“1) Shrimpers who can’t earn their livelihoods?”

“We will pay all legitimate claims.”

“2) Beaches spoiled, tourism ruined?”

“All legitimate claims.”

“3) Children sickened by oil fumes?”

“All legitimate claims.”

Ad nauseam.

To top it off, McKay had the gall to follow up this laughable interaction with a preposterous assurance: “this is not about legal words, it’s about getting it done and getting it done right.” No, sir, this is PRECISELY about legal words. Please refrain from lying under oath, Mr. McKay. It’s frowned upon.

The second most odious exchange of the hearing was when Transocean President and CEO Steven Newman was asked if this type of spill had happened before. He replied that the only incident he could recall was the Ixtoc spill. To his credit, that spill was the worst of this type, but this answer is incredibly deceitful.

You’re trying to tell me that that Steven Newman, presumably a lifelong oilman, the president and CEO of an offshore drilling company that specializes in deepwater drilling, has to go back 31 years to recall an incident like this one? I’ve never worked in the oil industry and even I know that THIS TYPE OF SPILL HAPPENED 8 MONTHS AGO (Halliburton is suspected to have caused that one too)! In fact, even the photographers in that hearing room knew about the Montara spill: Sen. Menendez brought it up earlier in this very hearing!

Note that the response was deliberately and delicately phrased (“the only incident I can recall“) so as to avoid committing perjury.

Even as oil is gushing into the Gulf of Mexico, the oil industry and their congressional allies are STILL trying to cast offshore drilling as a safe practice. This spill was not unconceivable and not unprecedented. Senators and oil executives repeatedly called this accident “unique.” The only thing unique about this oil well was that it was in even deeper water and even deeper underground than usual, so all the real risks associated with drilling and the complications of containment and cleanup for spills were MAGNIFIED!

It is also worth mentioning the conduct of the senators present:

The oil executives weren’t the only ones choosing their words carefully. When I tuned in, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) had the microphone. She was going to great lengths to avoid saying the words “oil” or “spill.” She even referred to the Exxon Valdez “incident.” This type of disingenuous wordplay is normally reserved for company spokespeople. Sadly, this is par for the Murky course.

Lisa Murkowski (R-AK): It is difficult (although sadly, not THAT difficult) to find a U.S. senator doing LESS for the American people and more for industry special interests.

Murkowski is often derisively labeled as (R-OIL) because of her industry ties. It is her “dirty air” amendment in the Senate that is attempting to strip the EPA of its authority (and indeed Supreme Court-issued mandate) to regulate carbon dioxide under the Clean Air Act. It came as little surprise when news broke early this year that the amendment had not been written by the senator’s staff but rather by oil industry lobbyists themselves. She was merely their mouthpiece. The things money can buy.

In her opening statement, Murkowski, the ranking minority member of the committee, explained why we need domestic oil drilling: “for the sake of our nation’s economy, for the sake of our national security, and this incident not withstanding, for the sake of our world’s environment.” The economic and national security impacts of domestic offshore drilling have long been shown to be literally negligible, but I am genuinely curious to hear how this congressional oil flack would spin drilling as anything short of toxic for “our world’s environment.” Too bad Murkowski wasn’t under oath too.

Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-AL) also took the opportunity to extol the virtues of domestic offshore drilling. I would tell you more about his questioning, but I really don’t think I could. When he had the microphone, I almost felt sorry for the industry executives; he never really put together a coherent sentence. The inflection in his voice was raised when he stopped talking, and he clearly expected them to respond, but I didn’t even understand what he expected of them. How fortunate, then, that the executives were coached not to give actual answers anyways.

Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-LA) was talking tough for her state. She is in a fierce primary against a much more liberal opponent, Lt. Gov. Bill Halter. But all her barking is election-year antics. No congressperson receives more money from the oil industry than Landrieu, and she continues to push the lie that offshore drilling is vital to our country – even as oil begins to wash up on Louisiana beaches. Her priority is making sure BP pays her voters quickly enough that she will be reelected to continue to act against our country’s best interests.

Sen. Robert Menendez (D-NJ) and Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) were on point and champions. They asked piercing questions and did their best to take the executives to task and get actual answers. Yet there is only so much one can do within this broken system.

Having watched some testimony before, I know that these proceedings were not that unusual. To me, this is not a defense of what transpired today but rather more proof that business as usual must change if we to move forward as a country, both in the context of this tragedy and more broadly. Congress is an inertial body, but a catastrophe of this magnitude demands action.

Full list of oil spill questions and answers here.

Conceivable and Precedented May 4, 2010

Posted by Jamie Friedland in Offshore Drilling, Politics.Tags: 2010 Oil Spill, Bahia de Compeche, blowout, Blowout Preventer, BP, Deepwater Horizon, Exxon, Exxon Valdez, Gulf of Mexico, Halliburton, Montara, Oil, Oil Spill

7 comments

***For newcomers: I have created a page of questions and answers about offshore drilling and this oil spill here.***

BP did not build containment devices before the disaster because it “seemed inconceivable” that the blowout preventer would fail.

– BP spokesman Steve Rinehart

“The sort of occurrence that we’ve seen on the Deepwater Horizon is clearly unprecedented.”

– BP spokesman David Nicholas

These are lies. Both of them. And I can prove it:

Blowouts aren’t inconceivable, they are actually fairly common.

I have already explained in detail how blowout preventers (the last line of defense against catastrophes like this) are known and even quantifiably proven to be woefully inadequate last lines of defense against this sort of disaster. A U.S. government report found 117 blowout preventer failures in just a 2 year period! And the oil industry knew this; each data point on that report’s survey was an actual blowout on an oil company’s offshore rig!

It is true that not every blowout leads to a catastrophic oil spill like this. Yet it doesn’t take an imagination to plot out a disaster scenario when highly pressurized, obviously flammable fuels come hurtling out of the ground with explosive force towards an oil rig. And the second lie is even more damning.

This “sort of occurrence” (the euphemism of the day) is not at all unprecedented: a similar blowout, oil rig fire and massive oil spill occurred off the northern coast of Western Australia just 8 MONTHS AGO. I want to swear here so badly.

Before I get into the more recent spill, I have to say that there have been plenty of significant offshore blowouts and oil spills (list here). The worst in history started on June 3, 1979. An exploratory well in the Bahia de Campeche (600 miles south of Texas) experienced a blow out. The oil and gas ignited, lighting the platform and soon causing it to sink. Unfortunately, that platform fell on top of the wellhead, severely hindering efforts to activate the failed blowout preventer (I know what you’re thinking: “failed blowout preventer? Those are the last line of defense! They never fail!” If you don’t understand that sarcasm yet, please read this).

The blowout preventer was ultimately closed, but it had to actually be reopened to prevent its complete destruction when some valves began to rupture. Between 10,000 and 30,000 barrels of oil gushed from that well every day for nearly 10 months until they finally capped the well on March 23 of the next year. 3.5 million barrels (147 million gallons) of oil were released.

As BP well knows, the precedent for this type of spill is well established. This oil well gushed for nearly 10 months from 1979-1980.

There have been many more blowouts since then, but lets jump to the most recent: a blowout on the West Atlas rig in the East Timor Sea created a gusher on August 21 just last year. Shockingly enough, a fire sparked. The spill continued for 74 days through November while it took crews 4 attempts to drill a relief well like they are now trying to do in the Gulf.

The “Montara” oil spill, as it was called, released an estimated 9 million gallons (Exxon Valdez = ~12 million gallons) into one of the world’s most pristine oceanic areas, but went largely unreported because of its remoteness.

The East Timor Sea was home to some of the world’s most iconic and endangered species including 15 species of whales and dolphins, at least 30 species of sea birds, and five species of sea turtles (it’s been an especially bad year for them). Furthermore, 10,000 communities and 7,000 fishermen rely on the area for their survival. Residents of villages in the region report skin problems and diarrhea from eating contaminated seafood. Fish catches have been reduced by 80%.

The Montara spill and the current crisis have a lot in common. The rigs involved were 2- and 3-years old, state-of-the art and reportedly safe. In both cases, early flow-rates were obviously understated. Both occurred in areas of vital ecological and even economic importance.

Yet all indications suggest that the Gulf spill will be far, far worse. The West Atlas rig didn’t sink. The flow rate in the Gulf is already much higher. And the Montara spill occurred in only 600 feet of water. The Deepwater Horizon rig spill is under more than a mile of water, and the oil deposit is more than twice as deep underground.

Recall that is took Australian crews 4 tries to drill a relief well. In case it hasn’t been made clear, that process involves drilling down to depth and then a long distance horizontally towards the first, leaking well. The goal of this extensive drilling is to locate and bore into the original pipeline, which is less than a foot across (at least for the East Timor pipe). So in the Gulf, crews will have to drill through 18,000 ft of sea floor beneath more than 5,000 of water. Then they have to drill laterally to find the pipe and pierce it from miles away. There is a reason this project is expected to take literally months, with barrels and barrels of oil leaking the whole time.

The biggest similarity between the two, however, is that the causes may have been identical. I wrote yesterday about Halliburton’s involvement in the “cementing” process for the Deepwater Horizon rig, and how experts believe that cracks in a faulty cementing job could be responsible for the current disaster in the Gulf. Interestingly enough, although the inquiry into the East Timor spill is not complete, investigators have identical suspicions about the cause of that spill. And I bet you can guess who was working on the cementing for that rig too – Halliburton.

Halliburton is still looking into the Montara spill. If we get the Gulf spill plugged, I would imagine they’ll start looking into this as well (although they won’t have to bother – we surely will). As Charlie Cray put it, “It’s starting to look like the only thing Halliburton can cap tightly is its own mouth.”

To be fair, BP’s lies are consistent with their actions. While they actively fought safety regulations that might have prevented this disaster, internal documentation suggests that their surprise at this incident is genuine. Stultifying and much closer to the actual meaning of inconceivable, but genuine.

In their 2009 exploration plan and Environment Impact Statement (EIS) for this well, BP wrote that it was virtually impossible for a major oil spill to occur that would cause serious damage to beaches, fish and mammals. They write repeatedly that it is “unlikely that an accidental surface or subsurface oil spill would occur from the proposed activities.” You know, because oil spills are virtually unheard of.

Even if a spill did occur, “due to the distance to shore (48 miles) and the response capabilities that would be implemented, no significant adverse impacts are expected.” And that’s it. Having said that, they made no plans about how they would respond if there was an “inconceivable” oil spill. Because what are the chances, really?

"Don't worry about our back-up plan. We don't have one. The rig will be 50 mi offshore, what could go wrong?"

That such a ridiculous EIS was accepted is further proof (not that any was needed after last year’s sex and drugs story broke) that industry is way too close with government regulators. No reasonable, independent citizen of this country would approve a drilling application that, instead of having a worst-case scenario response plan, simply said “that’s really unlikely, and we don’t think it will happen.” Incredible.

2010 Oil Spill Answers (Pt. 2) May 4, 2010

Posted by Jamie Friedland in Offshore Drilling, Politics.Tags: BP, Exxon, Exxon Valdez, fishermen, Gulf of Mexico, Halliburton, Offshore Drilling, Oil, Oil Spill, Oil Spill 2010, wildlife

4 comments

***I have added a new page to this site to let you more easily find the answers to your oil spill questions. It is the new “2010 oil spill/offshore drilling answers” tab next to the “about me” at the top of each page, or you can click here.***

In a previous post, I have addressed the following questions:

- What was the oil rig doing?

- What caused the explosion?

- How much oil is spilling?

- Where is the oil spilling from?

- Can we stop the spill? How?

- Could the spill get any worse?

I also answered why BP is responsible for this spill/explained what blowout preventers are, and, just a few weeks before this all began, I wrote a detailed post explaining why offshore drilling is dangerous and not an energy solution.

In this post, I will address these questions:

- What does this mean for people who live along the Gulf?

- What does this mean for the wildlife in the Gulf?

- How does this compare to the Exxon Valdez spill?

- How is Halliburton involved?

Also, the New York Times has a well-done, simple day-by-day map tracking the spill here.

What does this spill mean for the people who live along the Gulf?

This ongoing spill is going to prove catastrophic for many people around the Gulf. Not in loss of life, but through loss of livelihood. It has been estimated that the Gulf of Mexico is responsible for $31.8 billion annually in sustainable activities such as fishing (commercial and recreational) and tourism. As we have now seen, whatever money there is to be made from offshore drilling there, it completely jeopardizes the rest of the Gulf’s economic activities.

Unlike oil profits, which are extractive, one-time transactions that only enrich giant oil companies and their shareholders, the income from these other activities is sustainable and dispersed among millions of Gulf coast residents. It is how thousands upon thousands of fishermen and shrimpers and tourism operators have supported their families for decades and were planning to do so this year and into the future.

The iconic Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska offers some insight about what to expect for the Gulf region. 21 years after that spill, crude oil still remains on or just under the surface of some of the regions beaches. Fishing was out of the question for years. Indeed, many Gulf fishermen have already brought in their last harvest for some time to come: fishing has already been suspended in large parts of the Gulf. If fishery populations are decimated, those men and women might not be able to go to work for many years after we get the oil cleaned up.

That is what happened in Alaska after Exxon Valdez. Unable to work, fishermen remained at home as their bank accounts and family lives became depleted. Alcoholism, bankruptcy, suicide, domestic violence, and divorce rates rose significantly in the area. Men who have fished their entire lives and know how to do nothing else were suddenly powerless to provide for their families. And for what?

What does this spill mean for the wildlife in the Gulf?

The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee council estimated 250,000 seabirds, 2,800 sea otters, 300 harbor seals, 250 bald eagles, up to 22 killer whales died along with billions of salmon and herring eggs. Some species have recovered, some never did.

But the Gulf is not Alaska. Louisiana is the 2nd largest seafood-producing state in the country (after Alaska). In fact, much of the seafood served around the country, even in crab shacks along the Chesapeake Bay(!), is actually flown in from the Gulf. That will now stop. When such fragile ecosystems are disrupted so drastically, the effects can be very long-term.

The wetlands along the Gulf of Mexico, particularly in Louisiana, are not wildlife sanctuaries simply because they are a beautiful part of our country’s natural heritage. Many oceanic fish lay their eggs in the protection of those marshes. Crabs, shrimp, and oysters are completely dependent upon those coastal areas. If toxic oil reaches them, we will likely see population crashes across the spectrum of marine wildlife.

But the oil has devastating effects in the open water as well. The only living coral reef system in the continental U.S., fragilely situated along the Florida Keys, is imperiled. This spill spells doom for everything from sport-fishers’ Atlantic tarpon to the already decimated bluefin tuna population, shrimp, endangered sea turtles, essentially all Gulf commercial fisheries, migrating sea birds and marine mammals.

For a more detailed look at the threat to the region’s wildlife, I suggest Dr. Sally Kneidel’s May 2 post.

How does this compare to the Exxon Valdez spill?

Regardless of what happens in the next few days or weeks, Exxon Valdez and Horizon Deepwater will be the two worst oil spills in American history. As you may recall, the Exxon Valdez was an oil tanker that ran aground in Alaska, spilling nearly 11 million gallons of oil into the Prince Williams Sound. That accident was caused by the negligence of a captain who was accused of being drunk at the time. That is different from this situation.

However, the Valdez spill was also caused by a giant oil company’s refusal to adopt common-sense safety precautions that would cost a little extra money up front (although save the company literally billions by preventing oil spills), and in that respect, these two spills are very similar. Exxon took the inexplicable position of refusing to use double-hulled tankers even as the rest of the oil companies adopted the practice as commonplace and even demanded by law around the world.

More about that situation and Exxon Valdez in general here.

What makes this spill so terrifying is that its not really a spill. It is what’s known as a “blowout,” “gusher,” or sometimes a “wild well”: an uncapped well connected an oil reservoir under high pressure. Because of that pressure, oil will flow, sometimes violently, from the well as long as it remains uncapped. This brings us to the crucial difference between Exxon Valdez and this situation.

The Exxon Valdez was an oil tanker with a capacity of 1.48 million barrels of oil. Don’t get me wrong, that is a lot of oil and capable of immense ecological damage, but there was a finite amount of oil that could be spilled from that tanker. It is estimated that about 260,000 barrels spilled from the tanker. But in the Gulf, we are dealing with an ongoing spill from an entire reservoir.

Instead of the Exxon Valdez’s 1.5 million barrels, the reservoir in question is estimated to hold 100 million barrels of oil (4,200,000,000 gallons). These will continue to leak until the well is successfully plugged. And there is legitimate concern that the rate of the leak could increase by a full order of magnitude such that as much oil as spilled from the Exxon Valdez would defile the Gulf every 2 days. That is not a typo.

How is Halliburton involved?

Halliburton is the world’s second largest oilfield services corporation. Outside of the drilling industry, it is most [in]famous for being the subject of several controversies involving the 2003 Iraq War and former Vice President Dick Cheney’s lingering involvement with the corporation following his retirement as Chairman and CEO to run in the 2000 election.

Halliburton has confirmed that it provided numerous services for the Deepwater Horizon rig. Among them was a process known as “cementing”: plugging holes in the pipeline with cement. This practice is supposed to prevent oil and natural gas from escaping from the well at the drill site (except through the pipe).

The investigations about what happened and who is at fault have only just begun and obviously are secondary concerns after stopping this disaster, but experts are already suggesting that a faulty cementing job by Halliburton could be the culprit. Faulty cementing has already been identified as a major cause of blowouts, and Halliburton has actually been implicated in the massive blowout off the coast of Australia last year! I will be writing more about this and other blowouts later this week. It is no surprise, then, that the company is already charged in some of the first law suits that have been filed so far.

A government report released in 2007 examined 39 rig blowouts in the Gulf of Mexico between 1992 and 2006. Improper cementing was determined to be a contributing factor in 18 of the incidents.

More updates and answers to come.